Victorian Dance Ensemble at the Civil War Preservation Ball in the rotunda of the Pennsylvania Capitol Building

RESOURCES AND ARTICLES

Resources

Library of Congress Website - www.loc.gov

The “American Memory” section has the full text of hundreds of dance manuals from 1490 to 1920 at http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/dihtml/dihome.html

Several Civil War era manuals have been reprinted and are available for purchase in various Civil War shops and online:

Hillgrove, Thomas, A Complete and Practical Guide to the Art of Dancing, 1863, reprinted by Amazon Drygoods,

Davenport, IA, 1992.

Durang, Charles, The Fashionable Dancer’s Casket, 1856, reprinted by Applewood Books, Bedford, MA, 1996.

Beadle’s Dime Ball-Room Companion, 1858, reprinted by Sullivan Press, West Chester, PA, 1998.

Ferrero, Edward, The Art of Dancing, 1859, reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish, MT, 2005.

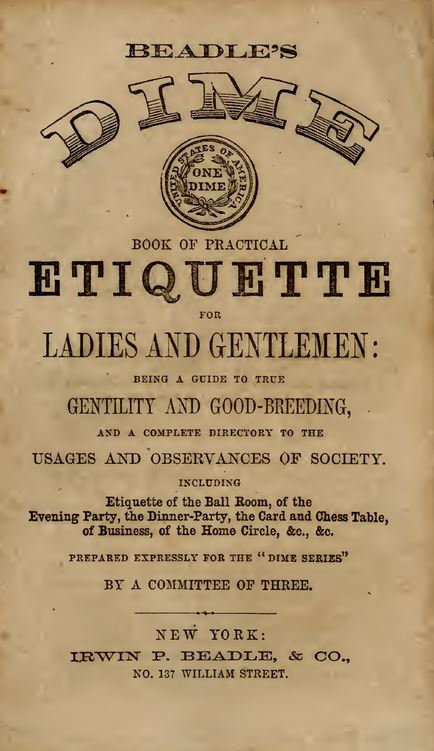

Etiquette Manual Reprints

Ladies' Book of Etiquette, Fashion and Manual of Politeness, 1860, reprinted by Amazon Drygoods, Davenport, IA, 1993.

Martine's Hand-Book of Etiquette and Guide to True Politeness, 1866, reprinted by R. L. Shepp, Mendicino, CA, 1988.

Beadle’s Dime Book of Practical Etiquette, 1860, reprinted by Sullivan Press, West Chester, PA, 2001.

Articles

(Below)

CIVIL WAR DANCING

SOCIAL INTRODUCTIONS AND TYPES OF BALLS

BALL ROOM ETIQUETTE

HEAVEN SAVE US FROM THE “ROUND DANCES”

CADET HOP AT WEST POINT

CAMP DANCING DURING THE CIVIL WAR

CIVIL WAR DANCING

U. S. Military Ball in Huntsville, Alabama from Harper’s Weekly, April 9, 1864.

A ball was held by the noncommissioned officers and privates of the 15th Army Corps of the Union Army.

The newspaper reported that:

Since the occupation of this place by General Logan, the soldiers have made many friends, and a few evenings since they gave a ball, at which a considerable number of ladies were present. The ball was well conducted and as full of enjoyment as any affair of the kind ever given in this place. The sketch gives the ‘Virginia Reel,’ danced with energy, and often performed as many as seven or eight times during the evening. General Logan attended the ball for a short time, and expressed himself pleased to see the quiet respect that was everywhere shown to the gentler sex by their brave attendants.

Dancing was enjoyed by almost everyone in America during the Civil War – North and South, young and old, rich and poor, urban and rural. During the 1860s, a ball was one way to forget, at least for an evening, the "fiery trial" of the Civil War.

Unlike modem dancing that is couple-oriented, dancing in the mid-Victorian era was much more "social". Most dances were done in the “open position” (couple standing side-by-side) in formations of circles, squares or lines, with the couple interacting with other couples. “Closed position” dances like the waltz and polka were considered scandalous in some communities and were generally done by young people and the urban fashionable upper classes.

It was considered ill-mannered to dance with the same partner all evening. Everyone at a ball had a social duty to mingle and to ensure that everyone else had a pleasant time. Although there were strict rules of behavior, they tended to add an agreeable degree of formality and decorum that has been lost in today's world. The Victorian Dance Ensemble is dedicated to recreating the grace and beauty of this bygone era.

Since there are no films of 1860s dancing, no one knows exactly how dances were performed. The Victorian Dance Ensemble has recreated its dances from a variety of sources, including period dance manuals, dance master's hand written notes, diaries and letters, and even drawings of dances. It is clear from primary sources that there was considerable variation in dancing, based on social class, urban or rural residence, age of dancers, geographic area, ethnic group, and whether the dancers took professional dance lessons.

The dances performed and taught by the Ensemble are its interpretation of the dances based on members’ research. Other dancers may have different interpretations and this is quite in keeping with the practice of the period. Several dance manuals and other sources often note that there are variations of particular dances. Etiquette of the time period, however, dictated that dancers should always follow the directions of the dance master. If you attended a ball and a dance was performed in a different manner than you were used to, you were expected to follow the dance master’s directions.

Dancing has relevance to the military side of the era since dancing could also be considered the first “drill” for young men who would become soldiers during the Civil War. The formation dances taught right from left, how to keep marching time, how to maneuver in a formation, and the importance of team work.

SOCIAL INTRODUCTIONS AND TYPES OF BALLS

Introductions were very important to class conscious nineteenth century people. They generally did not mix socially with other people much above or below their social class and never with anyone with whom they had not been formally introduced. A formal social introduction was made when one of your friends introduced you to a new person, with your permission (“May I introduce?”; “May I present?”). Once formally introduced, you could recognize and greet each other in public, you could visit the other person’s home, you could request assistance from the other person, and, most importantly for our purposes, a gentleman could ask a lady to dance. At a Ball, there was also an introduction merely for the purpose of dancing, which carried none of the social obligations of a formal introduction. There were three basic types of Balls during the mid nineteenth century. The type of Ball dictated the procedure for asking a lady to dance.

Private Balls were invitation only affairs, perhaps limited to family and close friends, social, fraternal or political organization members, or business, trade or craft members. At such an event, all were considered to be equal and fit company. Any man could ask any woman to dance, even if not formally introduced (although as a practical matter, most people were formally introduced at such events). If not otherwise engaged or fatigued, the woman should accept. To decline an invitation because the lady found the man “unacceptable” for some reason would be an insult to the host or hostess because it would imply that a man who was not a gentleman had been invited to the Ball. Etiquette books advised a lady to dance with an “unacceptable” gentleman so as not to embarrass the host or hostess, or the “gentleman” by drawing attention to him for being rejected.

Public Balls were open to anyone with the price of a ticket. Such Balls were common for raising money for various worthy causes and during the Civil War were widely used to support the war effort, both North and South. At such a Ball, if a gentleman had been formally introduced to a lady (either at the Ball or previously) he could ask her to dance. If a gentleman did not know a lady, he had two options to obtain a dance. If he knew someone who knew the lady, he could ask that person to discretely inquire if the lady would be amenable to a dance. He could then be introduced either formally or for a dance. If he was a complete “stranger” (the term used in etiquette books), he would apply to a Floor Manager for a partner. Floor Managers assisted the Dance Master in conducting the Ball and in particular arranging sets with the proper number of dancers. The Floor Manager would quickly “size-up” the man based on his demeanor, clothing and language, and locate a suitable partner of the appropriate class. The man would then be introduced to the lady for the purpose of dancing only. Again, a lady was expected to accept such an invitation to dance unless she already had a partner or was fatigued.

Master-Servant Balls were an old European tradition, where the lord of the manor held a Ball for his servants and tenants (and perhaps local townspeople). Some American employers continued the tradition of such dances for their agricultural and industrial workers. Such Balls, therefore, brought together a variety of social classes. Works of fiction (see Dickens and Austen), however, give the impression that such Balls were the great melting pot of society, where the lord danced with the scullery maid. In all likelihood, even though everyone was in the same room, there was probably little intermingling of the social classes. At such events, a variation of the Private Ball rule applies. Any man could ask any woman, but modified so that only “superiors” could ask “inferiors” to dance but not vice versa. Thus, the lord of the manor could ask the scullery maid to dance but the stable boy may not ask the lady of the house out onto the dance floor. The same rule would apply at a Military Ball involving a combination of officers, noncommissioned officers and enlisted men, and their ladies. A “superior” may ask an “inferior’s” lady to dance but not vice versa, unless invited to do so by the superior. (Note: In egalitarian America, all females were ladies. Traditionally in the British Army, however, officers had ladies, noncoms had wives and enlisted men had “women.”)

Invitations to dance were governed by strict rules, although there appear to be local variations. A universal rule is ladies did not invite gentlemen to dance. If they wished to dance with someone in particular, they told a friend, usually a male. The friend then discretely suggested to the gentleman that he ask the lady to dance. A gentleman desiring to dance with a married lady usually asked her husband first before asking the lady. Upon approaching a lady to ask for a dance, a gentleman bows and the lady acknowledges his greeting with a curtsey if standing or a nod if seated. A married lady need not rise from a seat to greet a gentleman, unless the man is considerably “superior” in social rank (such as a high ranking politician, military officer, or clergyman, a guest of honor or other important personage). Married ladies may offer their hand but generally the more public the event the less hand shaking. Unmarried young ladies do rise to greet all gentlemen but they do not offer their hand. At some stage in life, older unmarried ladies begin to obey the married lady rules (at this point she would be recognized as a “spinster”).

In asking for a dance, the gentleman always requests “the honor of a dance.” Etiquette books often point out the former tradition of asking for “the pleasure of a dance” was becoming less common. It can probably be assumed that in less sophisticated circles the older invitation was still in use. The gentleman should escort the lady onto the dance floor and return her to her seat (or wherever she desires) after the dance and thank her for the honor.

Hand kissing is not mentioned in Civil War period etiquette books and, therefore, was probably not done. An assumption can be made that if it was done the rules would have been specified in such books (as they are in later period books).

BALLROOM ETIQUETTE

Quotes from various manuals:

Never forget that ladies are to be first cared for, to have the best seats, the places of distinction, and are entitled in all cases to your courteous protection.

No young lady should go to a ball, without the protection of a married lady, or an elderly gentleman.

The customary honors of a bow and courtesy should be given at the commencement and conclusion of each dance.

After dancing, a gentleman should invariably conduct a lady to a seat, unless she otherwise desires: and in fact, a lady should not be unattended, at any time in a public assembly.

If you accompany your wife to a dancing party, be careful not to dance with her, except perhaps for the first set.

A gentleman should not address a lady unless he has been properly introduced.

In inviting a lady to dance, the words, "Will you honor me with your hand . . ." are used more now than "Will you give me the pleasure of dancing . . .".

Certain persons are appointed to act as floor managers . . . if you are entirely a stranger, it is to them you must apply for a partner.

Be very careful how you refuse to dance with a gentleman. A prior engagement will, of course, excuse you but if you plead fatigue, do not dance the set with another.

A gentleman introduced to a lady by a floor manager . . . should not be refused by the lady if she is not already engaged, for her refusal would be a breach of good manners.

Dance quietly, do not kick and caper about, nor sway your body to and fro, dance only from the hips downwards.

Lead a lady as lightly as you would tread a measure with a spirit of gossamer.

The fall of a couple is not a frequent occurrence in a ball room, but when it does happen it is almost always the man's fault. Girls take much more naturally to the graceful movements of the dance, and are, besides, more often taught in childhood than their brothers.

Never remain in a ballroom until all of the company have left, or even until the last set. It is ill bred, and looks as if you are unaccustomed to such pleasures, and so desirous to prolong each one. Leave while there are two or three sets to be danced.

It is best to carry two pairs of gloves, as in contact with dark dresses, or in handling refreshments, you may soil a pair, and thus will be under the necessity of offering your hand covered in a soiled glove to some partner. You can slip unperceived from the room, change the soiled for a fresh pair, and then avoid that mortification.

HEAVEN SAVE US FROM THE ROUND DANCES

“Round dances” (i.e., closed position waltzes and polkas) were considered scandalous in much of small town America during the Civil War. The following article was originally published in the Richmond Whig on January 15, 1863 and reprinted in the Philadelphia Inquirer of January 23, 1863. It was quite common in the mid nineteenth century for newspapers to reprint articles from other newspapers. This article expresses much of the sentiment of the older generation in regard to “modern” dances of the younger generation of almost any era.

A Lay Sermon on Dancing

Not only are dancing and junketing in bad taste at such a time as the present, but they are inhumanly disrespectful and foolish. If a father or a brother lay in mortal peril in an upper chamber, would it not be brutal in his children to be “cutting the pigeon wing” below stairs? Hundreds and hundreds of fathers and brothers are languishing in the hospitals of this very city, and thousands upon thousands of fathers, sons, husbands and lovers are exposing their lives in the field to save us from subjugation; and here we are, protected by the living wall of their dauntless breasts, kicking up our heels and tripping on the light fantastic toe in the most joyous manner. This is not the way to show a decent respect or a merely human sympathy for our suffering defenders. This is not the temper which will or ought to save a people from conquest.

Far be it from us to arouse needless fears or to repress innocent amusements. Properly guarded, dancing is a delightful, healthful pastime—infinitely better than the dry and dreary reunions where only conversations, half scandal and whole nonsense, is allowed. But if we must dance, let us confine ourselves to the old fashioned, decent and respectable dances—the cotillion and the like. Heaven save us from the “round dances,” as they are called—the loathsome products of a prurient French taste. We regret extremely to hear that these “round dances” are becoming all the rage at fashionable parties and at the “big hops” at the great hotels. Words cannot express our detestation and abhorrence of these dances. They ought not to be tolerated in the Confederacy. The girl who dances them might to take “Hamlet’s” advice to “Ophelia,” “Get thee to a nunnery.” They will do well enough for the romping female animals of Yankee land, but they ought to be scouted by every pure-minded and refined Southern lady.

We are getting corrupt too fast. What with cheating, extortion, drinking and dancing the round dances, we are leaping into the foul depths of Washington degradation at a single bound. If we must become rotten, let us rot a little less rapid. Let us taboo and kick out of respectable circles immodest and impure dances and them that dance them. If not, if we prefer to rush into the fashionable depravity of the European and Yankee capitals, let us by all means do it with an impetuosity and absolute license that will in some sort redeem our depravity. Let us have “the German” in our churches after morning service, let us introduce the “Cancan” into our private drawing rooms, and have “model artist” exhibitions every night in the parlors of the Exchange and Spottswood [Hotels].

CADET "HOP" AT WEST POINT

Harper's Weekly, September 3, 1859 - This engraving of a cadet “Hop” was based on a sketch by Winslow Homer. It depicts one of the dances held at the U. S. Military Academy, when the students are in a summer encampment on the plain to learn about army life in the field. Cadets received instruction from professional dance masters and are shown dancing in the new (and scandalous) closed position. The newspaper reported that:

Happily the rigors of military etiquette are mitigated thrice a week by balls or hops, which are given by the cadets to their friends and guests at Cozzens’s Hotel and elsewhere in the neighborhood. These gay parties are justly famed among the fair sex; for better and more indefatigable dancers than the cadets are not to be found even in New York. Pretty girls who go to West Point to spend a few days in the bracing air, and enjoy the lovely Hudson scenery, invariably declare that they never enjoyed any ball in their life so much as the Cadet Hops. The following gentlemen are the managers of the hops, and to them our artist desires to return thanks for the attention paid him on his professional visit: Nicholas Bowen, John R. B. Burtwell, Frank Huger, Wm. G. Jones, Josiah H. Kellog, Wesley Merritt, Horace Porter, S. Dodson Ramseur, John Adair, Nathaniel R. Chambliss, Campbell C. Emory, Charles E. Hazlett, William M’K. Leoser, Henry W. Kingsbury.

During the Civil War those cadets served on both sides: Huger commanded artillery units in Longstreet’s Corps. Merritt was promoted from captain to brigadier just before Gettysburg and served in the U.S. Army through the Spanish-American War. Ramseur became a Confederate major general and was killed at Cedar Creek. Porter served on Grant’s staff. Hazlett commanded the battery on Little Round Top at Gettysburg and was killed by a sharpshooter.

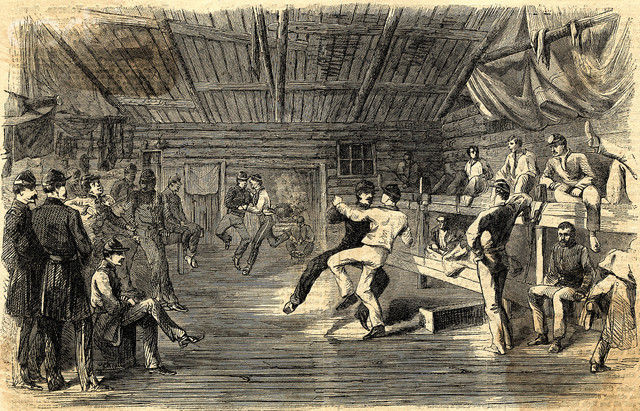

CAMP DANCING DURING THE CIVIL WAR

A Stag Dance from Harper’s Weekly, February 6, 1864

Our soldiers believe in the literal interpretation of the dictum of the Wise Man that "there is a time to dance." But to put their faith into works is not the easiest thing in the world, owing to the lack of partners of the feminine persuasion. However, by imagining a bearded and pantalooned fellow to be of "t'other kind," they succeed in getting up what they call a "Stag Dance," which is better than none, as is shown by the intense interest evinced by the spectators.

An excerpt from Charles W. Bardeen’s A Little Fifer’s War Diary describes as very “formal” dance held in camp by soldiers. Charles enlisted in the 1st Massachusetts on July 21, 1862 at the age of 14 as a drummer. He found he was not good at drumming and switched to playing the fife. In his book, Charles intersperses his diary notations with post war comments. In the spring of 1864, while encamped at Brandy Station, he wrote the following item in his diary for March 24 (boldface) and followed that notation with comments concerning the event:

March 24. Pleasant. Grand Ball. Went over and staid ‘till Supper. Did not dance. Got up in good style for privates.

[Bardeen’s post war comments] What I especially remember of this evening is the psychological effect of skirts. When it became known that the officers were to give us the use of their building for this ball some of the men sent home for various articles of women’s finery, including hoop skirts then in vogue. The men who dressed themselves in these garment were by no means the most feminine in the regiment, but the effect upon the rest of us was to produce the impulse of protection. The Excelsior brigade had not been invited, and toward midnight they attempted to force an entrance, using long poles as battering rams against an end door. As they pushed in and the fight began Jim McCrae happened to be walking on my arm, and I put myself in front of him as inevitably as if he had been a girl fifteen years old. But only for an instant. Jim was an Irishman of the Kilkenny type, red-haired, freckled face, blue eyes, always good-natured but always spoiling for a row. He swished his skirts out of the way, pulled up sleeves showing arms as remarkable for their whiteness as for their strength, and sailed into that Excelsior crowd with both fists. Only a few had got in and they were soon thrust our(t) again and the door securely fastened. The dance went on, and I think Jim and I finished the promenade, but the rest of the night I had a sort of sub-consciousness that in spite of his skirts he was quite able to take care of himself.